The process of co-design led to several adaptations, transforming the original disability checklist first into the DAC and thereafter developing the DAT, including the DAC and its intervention menu and training. The original checklist included four domains with 31 elements: universal design (7 elements), reasonable accommodation (10 elements), capacity building (8 elements), and linkages to care and support (6 elements). The answer option for each element included a simple binary format Yes/No with the option to choose ‘Not sure’ when applicable. It also had an additional field to identify “things that I can change/influence”. This provided the baseline for the first co-design cycle of expert consultations and development of the DAC version one (47 elements). The second co-design cycle led to further development and adaptations into the DAT, including the DAC version two (53 elements), its intervention menu, and training tools.

Process of co-design and field-testing

In the first cycle of the co-design process, the team assessed six disability audit tools, including the original disability checklist. Most tools focused on physical accessibility and communication, but the disability checklist stood out for addressing staff training and care pathway linkages. It was the only action-oriented tool suitable for resource-poor settings. Other tools provided valuable insights on international standards, which informed the adaptation of the checklist into draft DAC version one.

Using a draft version of the DAC, the team conducted six expert consultations and two district fieldwork meetings. They also presented at several District AIDS Council meetings, discussing the DAC as part of a broader QA tool for post-GBV services. While expert consultations focused on content, the fieldwork and district meetings were key to securing project buy-in and stakeholder permissions. As the quote below illustrates, feedback and identifying actionable steps were vital for gaining interest holder support.

When we [District AIDS Council] first started working with you [the research team], I was hesitant and concerned that we would not receive any feedback from you. However, you have shown otherwise, this meeting [dissemination meeting] is so important, and I really appreciate all the sharing, feedback, and information (District AIDS Council representative, project dissemination meeting)

The expert consultations revealed how experts perceived the DAC, its potential impact, and some potential challenges. Participants welcomed the DAC as a sensitisation and action-orientated tool in these consultations. They highlighted that it is important to address the gaps in accessibility and inclusion in both post-GBV clinical and healthcare services. Some went as far as conceptualising the DAC as a disability audit tool.

The Disability checklist- it’s a great one, but the most important thing would be “action”. It is up to the disability advocate action going forward (expert in GBV and HIV sector)

Children with disabilities are not catered for at TCCs [post GBV clinical service centres]. There are no interpreters. Even in court, these children do not get a fair chance in terms of telling their stories. The Disability audit tool is needed (expert GBV sector)

The consultation provided specific feedback on necessary adaptations regarding missing elements and language adaptations. For instance, experts highlighted that some disability groups were better considered than others in the original version, that language needed to be adjusted or that elements were missing and needed to be added.

Upon closer inspection, we found that these documents [original tool] are almost exclusively angled towards wheelchair users, with only nominal mention of any other form of impairment (expert disability sector)

The reporting system /patient feedback is missing in the tool (expert disability sector)

This process resulted in 16 additional elements being added to the original Checklist in phase one. The language was made more precise, and the care pathway linkage domain was meaningfully reorganised, starting from intake forms and moving to referrals, monitoring, and evaluation processes. During the expert consultations, participants also discussed the need to incorporate the DAC into existing QA tool processes. While the DAC was integrated into a post-GBV QA tool in this project, the need for integration into a South African QA tool for PHC services, such as the ideal clinic tool [52], was also discussed. Furthermore, experts highlighted the need to provide healthcare workers with training and sensitisation around disability following a DAC assessment. They said this training also has to include community workers, who could be laypeople.

We need to find a way in which the tool can incorporate the role of community health care workers since they are the ones that go from house to house engaging with people with disabilities (expert disability sector)

Sensitisation and special training are crucial when working with people with disabilities. The tool can advocate for training (expert disability sector)

The team conducted an additional consultation workshop in phase two to develop the DAC intervention menu. The DAC and a draft menu were shared in preparation for the workshop with the broader disability sector. As a result of including additional interest holders, the team had to navigate the needs of new groups who had not been engaged in the first cycle of the design process. In some cases, this revealed important new suggestions on how to adapt the DAC further while ensuring that the menu can also identify feasible solutions for an LMIC. For instance, the blind sector revealed that very few people can read Braille, and Braille is not necessarily helpful in emergencies. Hence, even though Braille signing might be an international standard, it would be better to find audio solutions that are accessible to all South African people who are blind. The workshop led to the consensus to include text-to-voice options or QR codes into the Checklist instead of Braille.

Braille signage on walls is generally not usable as most blind people will not be feeling around the walls in the case of an emergency – wherever possible, solutions that use voice instructions are preferable. Only approximately 10% of the VI [Visually impaired] population are Braille literate (expert disability sector)

At other times, suggestions included very detailed or high-tech items, which were not feasible for a simple action-orientated tool that aims to be short, feasible, and sensitise and initiate change in resource-poor settings. For example, one suggestion was to provide headphones at each clinic for people with hearing impairments. This proposal was carefully discussed with healthcare workers and DOH representatives, who explained that this is impractical both for operational reasons and due to hygiene concerns in a clinical environment. The group agreed that a more practical and straightforward approach would be to assess whether health facilities can connect people with disabilities to services that provide assistive devices, including hearing aids, and follow up on whether those referred received these items.

As a basic requirement, reception areas must be equipped with an FM [frequency modulated] system with headphones for those with hearing loss, including the elderly. Later phases may include a telecoil installed for use by those wearing hearing aids or cochlear implants (expert disability sector)

The process of considering everyone’s needs while aiming to develop a short, feasible and action-orientated tool required consultations with different interest holders and sometimes several back-and-forth consultations with the same interest holders until a consensus could be found. Allowing fieldwork participants to share their experiences with the tool was also critical. This sharing allowed the team to showcase the impact of the DAC on healthcare services and their staff and motivated workshop participants to find feasible solutions before adding too many elements to the DAC itself. In this process, fieldwork participants highlighted that healthcare workers are willing to make changes but need assistance and feasible ideas for adjusting their work environment. These reflections became important in leading the co-design to focus on a concise checklist that has a fitting intervention menu, hence guiding the practical implementation of change with feasible solutions that are locally available.

I have learned a lot from the process [DAC assessment] and was willing to make changes in our care centres. However, we needed more assistance and ideas on how to make facilities accessible and responsive to the needs of people with disabilities. An intervention menu for the DAC will help other managers like me to identify more opportunities for change and ensure that no one is left behind (manager of participating health care facilities, DAT consultation meeting)

The consultations and sharing of material also led to utilising the DAC version one outside the project. For instance, one organisation for people with disabilities utilised the DAC to assess its impact on their community facilities. Again, the feedback from these additional experiences was discussed in the DAT consultative workshop. The users’ reflections strengthened the emphasis on the simple design of the DAC, which enabled lay persons, including those with disabilities, to utilise this tool and sensitise and educate healthcare workers about possible changes.

Our team [Organisation of Persons with Disabilities (OPD) in DAT workshop] is assessing health facilities, and these did not have basic accessibility elements such as ramps. Yet the assessment process itself made an immediate impact and initiated change, in particular, as people with disabilities themselves were involved. The DAC is a useful tool as it can be applied by laypersons, including people with disabilities. It is an action-orientated tool that educates and sensitises both healthcare workers and organisations of people with disabilities about what is needed to change health facilities. We approached building contractors to build ramps so that they could have access to the facilities (OPD representatives utilising the DAC, DAT consultative workshop)

The combination of the broad and ongoing consultation over two years, engagement with different interest holders, sharing of fieldwork experiences and consensus-building process led to the development of the DAT, including the DAC version two, its intervention menu and training.

Features and adaptations in the design phases

The two co-design cycles led to several features and adaptations, including the overall DAC design (title, cover, number of elements, outlines), assessment elements, intervention menu for all four domains, and answer scales. It also included the development of appreciative inquiry support tools such as automated RedCap reports, narrative reports, the DAC intervention menu, and the development of facilitator training. An overview of the features and adaptations is provided in Table 4.

Implementation of appreciative inquiry

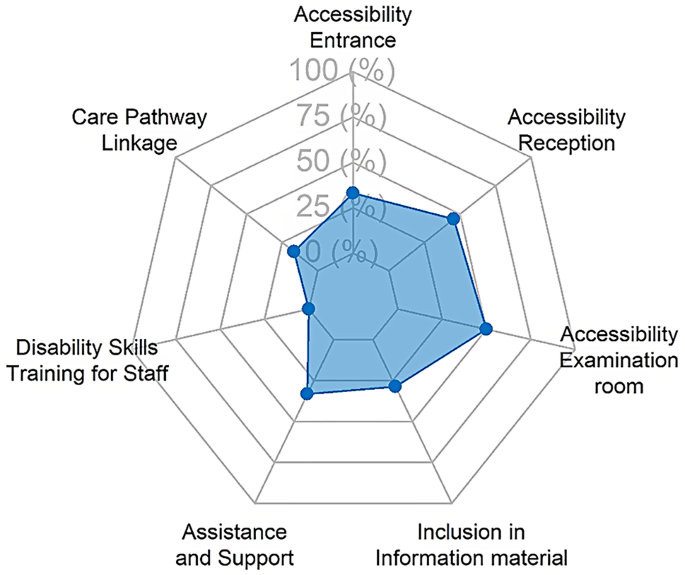

The DAC and its intervention menu were implemented in a two-stage process during a ‘DAC-visit’. In the first stage (assessment), facilitators used the DAC to assess the level of accessibility and preparedness of the health facility to service people with disabilities. Facilitating this process required assessment and synthesis skills from facilitators. The team developed a RedCap data entry and report template to support this process and designed a step-by-step facilitator guide and SOP. The RedCap report rapidly synthesised results with automated result tables and a simple visual spider diagram (Fig. 2). These were available to the team in real-time, directly after the DAC assessment. The fieldwork revealed that mobile data and a portable printer were crucial for this implementation as some health facilities did not have reliable internet, printers, or electricity. The simplicity of the spider diagram report emerged as an important feature for providing quick feedback regarding achievements and gaps (Fig. 2).

Example of results in spider diagram for one health facility, results in percentage

The second stage (reflection) focused on discussing the results and finding feasible solutions to initiate change. Some lay facilitators found this process challenging, in particular when they struggled with capacity at under resourced clinics or if couldn’t identify feasible local solutions. This challenge highlighted the need to develop more support for facilitators. To address this, the team formalised the implementation of the appreciative inquiry techniques. It also engaged interest holders in a second design process to develop the DAC intervention menu (this had not been planned at the project’s outset). The team discovered that the appreciative inquiry technique was most effective when emphasising the participant’s strengths, particularly their agency to initiate change. Facilitators were trained to identify their agency (define) with facility staff and work together to identify potential approaches to improve their facility (dream). The intervention menu, mirroring the DAC, proved essential for proposing feasible solutions during the appreciative inquiry process design stage, where participants determined which elements to focus on and how to address them. This step-by-step process was vital for initiating willingness to change. Participants expressed that they initially expected poor results in the assessment, so the structured approach, guiding them from defining their strengths to identifying actionable solutions, was particularly valuable.

I knew, based on your questions, that we would not do well, but I appreciated the fact you came and showed us what needs to be done (Data Manager)

It was a good experience for us, and we are hopeful that step-by-step gaps identified will be closed (Operational Manager)

Furthermore, the fieldwork revealed that sharing and explaining results in narrative reports were important design aspects. While the Redcap reports provided quick, simple overviews of results through tables and spider diagrams, descriptive narratives explained the synthesised results and proposed solutions.

The report was very informative. I liked the background and table results, and they were easy to understand because we had a brief understanding of Redcap results (Nursing Assistant manager)

Findings in the post-design phase

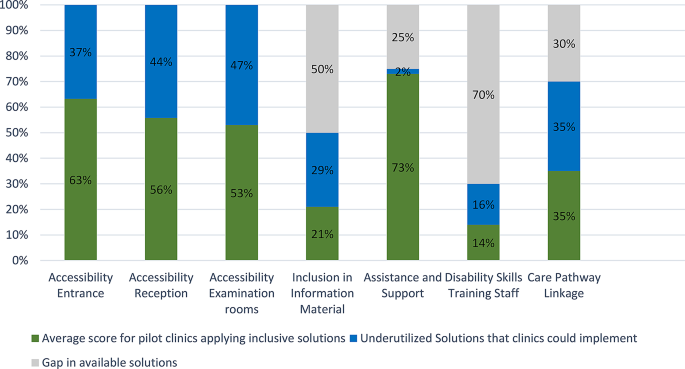

After fieldwork completion, the team synthesised the results in both design phases. This synthesis included descriptive statistics of the DAC results for all health facilities combined with mapping of available solutions in the DAC intervention menu. This process revealed two developmental aspects. Firstly, many health facilities were not utilising available solutions, even in the domain of universal access, which is regulated by building and facility standards that can be implemented in South Africa (Fig. 3, light blue bar part) [53]. The full results will be published in an upcoming paper.

Secondly, the process revealed that some solutions were unavailable for certain elements in the DAC domains. This gap was evident for 50% of accessible/inclusive information elements, 25% of disability-related assistance elements in the reasonable accommodation domain, 70% for the capacity of staff elements (accredited disability skills training for staff), and 30% of essential care pathway linkages elements (Fig. 3, light grey bar part). These gaps included essential elements such as accredited disability etiquette training for health care workers (or other training), a disability screening tool for PHC, and patient forms that collect information on disability and reasonable accommodation needs [44, 45]. Hence, the post-design phase revealed further gaps that need further research and innovation.

Pilot results and gaps in available solutions for all pilot clinics combined

The post-design phase also revealed important process information related to training needs for healthcare workers, acquisition challenges, and facilitator experiences.

For example, the need to develop accredited training on disability etiquette and disability and GBV had already been identified as an important next step during the fieldwork phases [44, 45]. The team piloted such training, which participants in the dissemination events welcomed, as they felt it would enable them to understand how to address the gaps in their facilities. Translating results into training opportunities was also perceived as an appropriate way to give back to participants and their facilities. It, therefore, could be a meaningful aspect of co-design.

I am also very excited about the ongoing training, very soon I will be able to close more gaps in disability in our clinic (nursing manager)

Post-design consultations also revealed how participants at sites had used the information from the pilot testing process and what aspects they implemented. For instance, some facility managers reported that the DAC assessment process gave them space to reflect and understand why people with disabilities do not come to their facilities. It also allowed them to identify errors in the procurement and building of structures and feasible solutions to fill identified gaps.

The DAC assessment process offered me an opportunity to reflect on my personal and professional role in the facility, and I realised that I had missed important elements of inclusivity and accessibility in our care centres. Clients with disabilities may not come to our facilities because they are not accessible, don’t respond to their health needs, or people with disabilities simply cannot get there. We have made mistakes when purchasing items such as doors, furniture, and bathroom sets. I discovered that our processes need updating as they don’t capture crucial information such as disability status and needs. I found that there were easy wins hidden within the DAC, such as linking to organisations for persons with disabilities (OPDs) or sending staff for disability etiquette training (manager participating health care facility, DAC meeting)

Post-design consultation in phase two also revealed why some existing solutions are challenging to implement. For instance, height-adjustable examination beds are available in South Africa but are more expensive and, therefore, less often ordered. Hence, participants expressed that this information needs to be further communicated and inform the country’s procurement system, which needs to negotiate better rates. Further consultations with DOH were therefore recommended.

Finding solutions for our gaps is important; some are easier implemented than others, and some need industry adjustments. For instance, I have tried to get height-adjustable beds, but they are very expensive. We need to be able to procure them at better rates (Department of Health representative, end of project consultation meeting)

The post-design work also revealed important aspects of the DAC facilitator training in cycle two, which included young people with disabilities who were new to research and facility assessments. The engagement with these facilitators revealed that ongoing training and support for the facilitators during implementation is important as more questions arise during the fieldwork. It also revealed that the DAC intervention menu was essential to support these DAC facilitators during the appreciative inquiry process.

Initially, I was nervous during the first visit, worried about making mistakes since it was my first time in the field… I had to learn about concepts such as screening tools to identify impairments in children and adults… The Intervention menu was instrumental for me in providing recommendations and conducting the DAC. After visiting several clinics, I gained confidence, became more comfortable with the process, and felt more at ease asking and answering questions (young person with disability facilitating DAC testing)

My experience working with the DAC was at first very nerve-racking because I was not confident enough. Through familiarising myself with the DAC and with continuous support from the team, I gained confidence and felt empowered to deliver a tool that assists healthcare providers in making their clinics more inclusive and accessible for people with disabilities (young person with disability facilitating DAC testing)

link