We developed a 3d interactive web application enabling participants to furnish an empty virtual living room using a predefined set of furniture items. This approach is similar to mobile games that let users design virtual spaces; however, our application provided control over several key aspects. Participants could freely select and arrange furniture, with no restrictions on the number of items they could use. At the same time, we ensured experimental control by providing a balanced and systematically structured set of items, allowing us to investigate individual design preferences under controlled conditions. The entire experiment was conducted in the German language. Therefore, all materials, including the questionnaires and the texts in the developed application, were presented in German.

Conditions

We provided participants with a balanced set of furniture items, allowing them to furnish their ideal living room freely. The furniture set was systematically controlled along two key dimensions: form (angular vs. curved) and style (modern vs. classic).

-

Form: Angular items predominantly featured 90° angles, while curved items had no hard edges.

-

Style: Modern items followed a minimalistic design, whereas classic items were more detailed, including embellishments and ornamentations.

Each furniture item was characterised by a combination of form and style, resulting in four distinct categories: angular-modern, angular-classic, curved-modern, and curved-classic. To ensure a controlled comparison, we designed each item to have a matching counterpart within its category. For instance, the angular-modern armchair had a corresponding curved-modern version that was identical in all aspects except for its form. Additionally, all items within each category were size-matched to maintain consistency across conditions. We used the same 3d furniture objects that were employed in previous studies to investigate form preferences in interior design7,8,21. We added two additional sets of furniture, matching the previous ones, to offer participants a larger selection.

Hypotheses

If participants consistently chose one form or style over the other, we interpreted this as an indication of a preference. In the absence of such a preference, we expected their choices to be distributed evenly across categories (e.g., 50% angular, 50% curved). We hypothesised that participants would prefer curved over angular objects, selecting a higher proportion of curved items. Building on previous research suggesting sex-related differences in contour preferences8,20, we further hypothesised that female participants would show a stronger preference for curved furniture than male participants.

We treated style (modern vs. classic) as an exploratory factor without a directed hypothesis, given inconsistent findings in prior research6,8,18. We also examined in an exploratory manner whether preferences for form and style varied across different furniture categories. Finally, we hypothesised that personality traits would be associated with participants’ form and style preferences.

Interactive web application

The interactive web application was developed using Unity (version 2022.2.3f1, The application centred around an empty virtual living room that participants could furnish freely. An overview of the web application is provided in Fig. 1, highlighting all action panels. The room had a size comparable to 7.4 × 5.4 m, and a height of 3 m, featuring a door in one corner and three windows on the opposite wall. The window view was kept neutral to avoid any bias it might have on the furniture placement within the room. Participants could navigate the space using the keyboard keys W, A, S and D and adjust their camera perspective by holding the right mouse button. A camera button in the top-right corner allowed switching between bird’s eye and first-person views (see Panel 2 of Fig. 1). Additionally, a toggle button in the top-left corner enabled participants to switch between angular and curved versions of the windows and door trims (see Panel 1 of Fig. 1). The option to modify the form of these room elements was included for consistency with preceding studies using similar stimuli7,8. A video demonstrating this application can be found here: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/27TXP.

User Interface of the 3d web application. 1: Toggle switch to change the form of the windows; 2: information button for instructions; save button (accessible from 30 min onwards); camera button to switch between bird’s eye and first person view; 3: furniture categories and items to select from; from left to right: armchairs, chairs, sofas, ceiling lamps, floor lamps, table lamps, cabinets, tables, small tables, plants, paintings, candles, vases, and decorations; 4: action buttons to confirm items status, rotate, change colour or delete item; 5: options to modify material and (if applicable) fabric of the item; 6: buttons to move the selected item within the room.

Furniture selection and categorisation

Furniture items were displayed at the bottom of the screen (see Panel 3 of Fig. 1), organised into the following categories: armchairs, chairs, sofas, ceiling lamps, floor lamps, table lamps, cabinets, tables, small (side) tables, plants, paintings, candles, vases, and decoration (which included baskets, carpets, and cushions). Most categories contained eight items, with two per form-style combination (angular-modern, angular-classic, curved-modern, curved-classic). Exceptions included the table lamps and paintings, which had only one item per form-style combination (four in total). Decorative items (baskets, carpets, and cushions) had only one version per form, without a style distinction, and plants had one angular-shaped and one curvilinear-shaped option, but with varying pot styles and materials. A full list of all available furniture items (102 in total) is provided in the supplementary material.

Interaction and customisation

Participants could select furniture items from the interface at the bottom of the screen. Upon selection, the item appeared in the centre of the room, marked by a blue circle indicating it was active for modification. Participants could then move the item freely within the room, rotate the item in 90° increments, and change its material and fabric (if applicable). Once an item was positioned, participants could confirm their placement and close the action buttons (see Panel 4 of Fig. 1). However, previously placed items could be selected and modified again at any time.

Material and fabric options

A limited selection of materials and fabrics was offered (see Panel 5 of Fig. 1). For materials, we included two wood options (light and dark wood), two metal options (silver and gold), and two neutral options (black and white). For fabric, we included three neutral options (grey, white, and black), two warm colours (pink and orange), and two cold colours (blue and green). All fabric colours were matched for luminance to ensure equal contrast across conditions. While the material selection was available for all furniture items (besides carpets), the fabric selection was only available for upholstered items (such as sofas and armchairs) and carpets.

Participants

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the local ethics committee at the Center for Psychosocial Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, in Hamburg, Germany (reference number: LPEK-0657). The experiment was conducted online and hosted on the Prolific platform ( where it was made available to participants residing in Germany who were of legal age. A G*Power30 analysis indicated a sample size of N = 147 for a one-sample t-test with an expected effect size of 0.3. Due to anticipated exclusions due to technical errors, we decided to aim for 200 participants after applying exclusion criteria. At the beginning of the experiment, participants were required to confirm that they had no neurological or psychological disorders, were not affected by red-green blindness, and would use visual aids (e.g., glasses) if needed. We excluded participants if they: withdrew consent during the study, placed furniture in an illogical or nonsensical manner (e.g., a sofa facing a wall), or furnished the room with fewer than four items (although there was no strict minimum requirement). For some participants, we experienced technical issues that resulted in missing data on furniture placement. Hence, we excluded these participants from further analysis. A total of 263 participants completed the experiment. After applying exclusion criteria, the data of 67 participants were removed (63 participants due to technical issues resulting in missing data on furniture placements and four participants due to illogical placement of the furniture), leaving 196 participants’ data for further analysis. Of these, 99 indicated male as their sex assigned at birth (Mage = 29.6, SD = 8.33), with ages ranging from 18 to 59 years, and 97 indicated female (Mage = 29.2, SD = 8.54), with ages ranging from 19 to 63 years. In total, four participants identified differently from their sex assigned at birth. For the subsequent analysis, we focused on sex assigned at birth; therefore, any references to sex or sex-related differences pertain to sex assigned at birth. Participants were compensated with 6 GBP upon completion of the experiment.

Procedure

At the beginning of the experiment, participants were introduced to the study procedure and data handling policies. After providing informed consent, they completed a tutorial that guided them through the web application’s functionalities. The tutorial explained how to navigate the room, select and place furniture, and adjust materials and fabrics. Participants were instructed to design a living room according to their personal preferences, and they could revisit the tutorial at any time by clicking the information button in the top-right corner of the application.

Once the tutorial was completed, participants proceeded to the furnishing task, on which they were instructed to work for at least 30 min. During this period, they could freely arrange and customise the furniture in the virtual living room. To ensure that all participants had sufficient time to engage with the task, the option to save and proceed was only enabled after the full 30 min had elapsed.

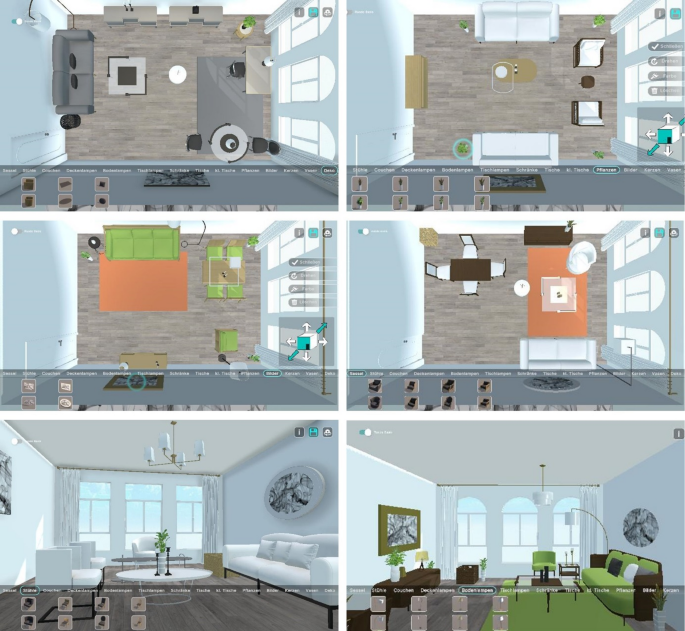

After completing the furnishing task, participants were directed to a questionnaire implemented using Inquisit by Millisecond (version 6.6.1, The questionnaire collected demographic information, details about participants’ current and preferred living environments, and responses to an adapted version of the Vienna Art Interest and Art Knowledge Questionnaires31, modified to focus on architecture21. We included the VAIAK to assess individual differences in knowledge in art and architecture, building on previous research showing that form preferences can differ between experts and non-experts19. To assess personality traits, we used the German version of the BFI-224,32, which consists of 60 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree a little; 3 = neutral; no opinion; 4 = agree a little; 5 = strongly agree). The entire experiment took approximately 40 min to complete. Examples of some resulting furnished rooms are provided in Fig. 2.

Examples of furnished rooms from study participants. The top and middle rows show rooms from a bird’s-eye view and the bottom row from a first-person view. Participants were free to switch between these perspectives at any time. The screenshots of the final rooms were taken after participants spent at least 30 min furnishing the rooms and clicked on the save button to proceed with the experiment.

Data analysis

This study was preregistered ( To quantify individual preferences, we calculated the percentage of selected curved items and modern items for each participant. Since each furniture item was categorised as either angular or curved, and either modern or classic, these percentages indicate whether participants exhibited a preference for one category over the other. While the application also allowed changing the form of the windows and door frames (see Panel 1 of Fig. 1), these options were not part of the main furnishing interface, and due to a bug in the application, participants’ choices were not saved; therefore, this data was not included in the analyses. To test for overall preferences, we conducted two-sided one-sample t-tests against 0.5 (indicating no preference). Further, we conducted two-sample two-sided t-tests comparing form and style preferences between male and female participants. Additionally, within each subgroup, we performed one-sample t-tests against 0.5 to test for preferences among male and female participants separately.

We summarised the data by furniture type, form, and style and conducted chi-square tests to evaluate whether form and style preferences varied significantly across different furniture types.

Finally, we conducted multiple linear regression analyses, using the percentage of selected curved items as the dependent variable and scores from the five BFI-2 dimensions (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, negative emotionality, and open-mindedness) as independent variables. We repeated this analysis with the percentage of selected modern items as the dependent variable.

Due to a technical issue during data collection, only 50 of the 60 BFI-2 items were initially recorded. To address this, we contacted participants after the experiment and asked them to complete the missing 10 items, offering a 1 GBP bonus payment for participation. However, only 100 participants provided the missing responses. As a result, analyses involving BFI-2 scores were conducted on this subset of N = 100 participants with complete personality data.

All analyses were conducted in R Studio (version 2024.09.1, R version 4.3.0).

link